80 years ago this year, a group of top scientists from the US, Britain and Canada collaborated on developing a means of protecting Allied naval ships from German torpedoes. Called the Philadelphia Experiment, the event was one of the pivotal moments of World War II. Shrouded in secrecy, many have fantasized about what happened at the naval yard in Philadelphia in the late summer of 1943. Stories abound of a ship, the USS Eldridge that vanished in the night, teleporting to another place beneath a magical green glow. Sailors that disappeared in front of people’s eyes.

The truth is as amazing as the fantasy. It includes one of our own: Canada’s “walkie talkie” inventor, Donald Hings, and it all started - at least for Hings - with a lucky break which facilitated his attendance at Chesterfield School for Boys in North Vancouver.

Donald Hings, 1940, courtesy of the Hings family.

Born in 1907 in Leicester, England, Donald was only three when his mother migrated to Canada. Separated from her husband after a short-lived abusive marriage, Winifred Mary Hings was tasked with bringing up a young boy on her own. Initially, she and Donald settled in Lethbridge, Alberta, before relocating when Donald was about ten years old, to Vancouver. Winifred found work as a bookkeeper with the British Columbia Electric Railway, whilst lodging at 646 West 10th Street. Donald attended Chesterfield School, a private school for boys in North Vancouver, likely as a boarder.

Chesterfield School with teachers and pupils, early 1920s. Donald Hings is in the middle row, 3rd from left. Public Domain. Identification confirmed by the Hings family.

Chesterfield House, designed by architect Henry Blackadder in 1913, is the last reminder of this once prestigious school at the corner of Chesterfield Avenue and Osborne Road. As described to the author of this article by Donald’s daughter, Doreen, now aged 88, Donald was sponsored at Chesterfield by Charles Dore, a clerk at Lethbridge Public Works Department who had become a family friend. Crucially, given the direction his career was to take, Donald was introduced to wireless communications. By the age of 14 he had built his own crystal radio set. It was to be a lifelong interest that - coupled with his instinct for tinkering - would lead to amazing discoveries.

Donald left Chesterfield, aged 15, helping his mother make ends meet by working as a labourer in a Coquitlam veneer plant. On the side, he assembled and sold crystal radio sets and undertook a two-year wireless communications course at Sprott Shaw Business Institute. As described by Donald’s daughter, Doreen, Sprott Shaw was at that time a small commercial school above a tailor’s shop at 336 West Hastings Street, between Vancouver’s downtown Woodwards and Spencer’s department stores. Classes appear to have been taught by Walter Lambert, a radio enthusiast who was later to become head instructor of the Vancouver School Board’s wireless course at King Edward High School. It was to be the last of Donald’s formal education. In his late teens, a land inheritance drew him and his mother to the interior near Rossland, BC. Once again, this may have been beholden to the generosity of family friend, Charles Dore whose will, following his death in 1929, records Winifred as his sole beneficiary.

Donald worked as a superintendent for a plywood company in Trail for several years, whilst continuing to pursue his interest in radios. In 1930, he landed a job as a radio engineer at the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company (CM&S), where he was given rein to develop his two-way radio. At the time, the company lacked the means to effectively communicate between its Trail headquarters, its fleet of float planes and army operated signal stations in the Northwest Territories. Donald’s innovation used a crystal to produce an oscillating circuit. Without realising it, he had invented the world’s first radio frequency current amplifier. Concurrently, he designed a drop-type aircraft antenna, and a two-channel transceiver employing his crystal oscillator. For the first time, CM&S pilots could talk to their dispatcher at Trail over distances up to 1,000 miles.

Donald Hings working on a prototype of his “walkie talkie” for military use in 1942, courtesy of the Hings family.

Initially described as a “packset”, Donald’s portable two-way radio was later to be known as the “walkie talkie”, used by allied troops to communicate with each other during the second world war. It was the catalyst for an illustrious career pioneering developments in communications, recognized after the war by an MBE from the British Government and, later in life, by the Order of Canada.

But how does this story fit with the 1943 Philadelphia Experiment you may ask?

USS Eldridge at full speed ca 1944. Courtesy, US Naval History and Heritage Command.

It all stems from a story told by Donald Hings to his grandson and a photograph found in his effects, but to get to the bottom of it, we need to know what came before.

When war broke out with Germany in September 1939, Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister quickly realized that protecting shipping routes across the Atlantic was key to victory. Allied ships were being sunk in scores, many blown up without a German U boat even in sight.

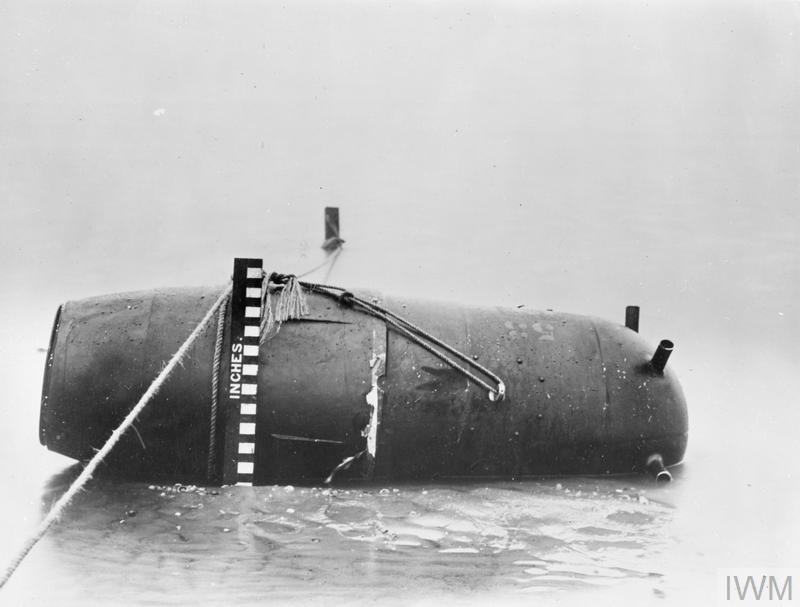

German magnetic mine, Shoeburyness mudflats, 23 November 1939. Courtesy, Imperial War Museum, England.

Amidst the carnage, one piece of luck went the Allies’ way. In November 1939, a German aircraft dropped an unexploded mine into the mudflats of London’s Thames Estuary. Inside, bomb disposal experts found a mechanism that sensed changes in magnetic field. It was a sea mine, designed to explode when a ship passed over the top of it.

British scientists found a solution: degaussing (i.e. decreasing or eliminating) a ship’s magnetic signature by running charged electric cables around its hull. A vessel could be protected for months until it once again built up a field. Boats that sailed during the British army’s retreat from Dunkirk in 1940 were degaussed in a marathon four-day effort at degaussing stations.

The lead up to the Philadelphia Experiment goes back further. Concerned about Hitler’s territorial ambitions, the British Government had, in 1935, set up the Tizard committee. Led by Henry Tizard, and including Nobel winning scientist Dr. Archibald Vivian Hill, this committee examined the feasibility of a ‘death ray’ - using electro-magnetic radiation to bring down invading aircraft and their pilots. When this didn’t work, Robert Watson Watt and his assistant, Arnold Wilkins, found an alternative. The 1935 Daventry Experiment proved that radio waves would bounce off an aircraft to a receiver. They called it radar.

By 1939, 20 radar stations circled Britain. Called ‘Chain Home,’ it could identify enemy aircraft as they crossed the coast.

Early radar was enhanced in 1940 by the development of the cavity magnetron. Microwave radiation could be emitted in high power from miniaturised devices. It opened up the possibility of night vision for aircraft, and radar on board ships.

Original cavity magnetron brought to the US by the Tizard Mission in 1940. Public Domain

Determined to have the Americans in the war, Churchill agreed to Dr. Hill’s recommendation that the technology should be shared. In September of that year, the Tizard Mission went to the US. Inside a metal box they carried a cavity magnetron and details of Frank Whittle’s newly discovered jet engine.

Collaborative ventures emerged, including an International Commission at the US’s National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) at Langley, Virginia.

And now to the photograph.

International Commission for the US National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), Langley, Virginia, USA, dated 29 May 1943. Dr Edgerton and Dr Hill identified. Donald Hings (back row, second from right). Courtesy of the Hings family.

As shown above, a photograph dated 29 May 1943 found in the effects of Donald Hings identifies scientists from the US, Canada and Britain, including Dr. Hill, Dr. Edgerton, an American professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and (crucially for us in terms of this article) the man himself: Donald Hings, Canada’s inventor of the “walkie talkie”.

The details of this elite group of scientists’ research have been withheld on the grounds of secrecy. Light on the matter is, however, cast by French scientist and ufologist, Jacques Fabrice Vallee who, in 1994, wrote an article entitled “Anatomy of a Hoax”. Published in the Journal of Scientific Exploration, this article explains what happened in the Philadelphia Experiment, the truth behind the fantasy.

A previous article by Vallee had invited readers to contact him if they had information, and Vallee’s 1994 article focuses on a letter he received in 1992 from Edward Dudgeon who served in the US Navy from 1942-1945.

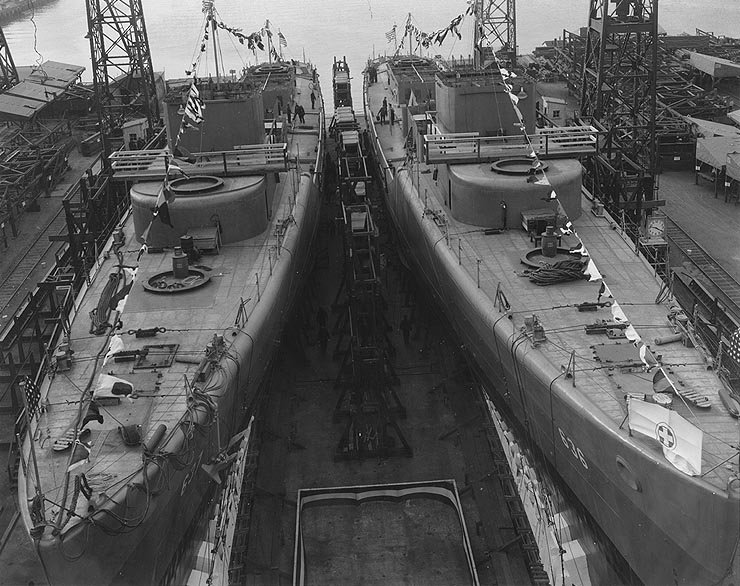

Philadelphia Naval Shipyard Dry Dock 1942. Public Domain.

Dudgeon was an electrician’s mate on the USS Engstrom, which was in dry dock in Philadelphia harbour in the summer of 1943, alongside the USS Eldridge and two other Destroyer Escorts, the USS Dobler and USS Doneff. The Engstrom was being fitted with high-torque screws. As Dudgeon describes in an interview with Vallee “the new screws made a sound of a different pitch, which made it harder for the submarines to hear us. They also installed a new sonar for underwater detection, and a device we called a “hedgehog” which was mounted in front of the forward gun mount on the bow. It fired depth charges in banks of 24 to 30 in a pattern, and could cover 180 degrees as far as about a mile away. That was one of the secrets.”

Dudgeon attributes the origin of rumours about “invisibility” to idle sailor talk. “We were trying to make our ships invisible to magnetic torpedoes, by degaussing them. We had regular radar and also a “micro-radar” of lower frequency. They could detect submarines as soon as they raised their periscopes or came up for air.”

The degaussing process is described. “They sent the crew ashore and they wrapped the vessel in big cables, then sent high voltage through these cables to scramble the ship’s magnetic signature.”

Philadelphia Experiment folklore cites two vanishing sailors and the ‘disappearance’ of the Eldridge in a mysterious green glow to emerge in Norfolk, before reappearing miraculously back in Philadelphia. Dudgeon’s explanation is simple. A fight broke out in a tavern in early August 1943. Some sailors from the Eldridge and Engstrom bragged about the secret equipment and were told to keep their mouths shut. Dudgeon and another sailor were there, drinking, but underage. As soon as trouble began, the waitress shooed the two of them out of the back door and later denied knowing anything about them.

The Eldridge left at 11pm that night, making the six-hour journey to Norfolk via the Chesapeake-Delaware Canal, rather than the longer journey by sea. The Engstrom followed, passing the Eldridge on its way back. Norfolk was where the US Navy loaded ammunition. It was a four-hour process. Both ships were back in Philadelphia harbour by the next day.

The Engstrom, together with the other ships went to Bermuda in July 1943 and returned in early August. Dudgeon confirms that “during that time the Engstrom was caught in a storm that created a display of green fire accompanied by a smell of ozone. The glow abated when it started raining.”

His version of events rings true. St Elmo’s fire, where objects glow during an electrical storm, is a proven phenomenon.

The fantasies can be put to rest. The Philadelphia Experiment gave Allied shipping an edge in winning the war, thanks to the brilliance of the scientists involved. We on the North Shore can be thankful for the role that North Vancouver’s former Chesterfield School for Boys played in setting Donald Hings on a path to helping in this success.

Donald Hings at Chesterfield School early 1920s. Courtesy of the Hings family.

Chesterfield School for Boys Today

The Main House of the Chesterfield School for Boys was converted into 12 apartments and in 2010, it was legally protected through a Heritage Revitalization Agreement, whereby the lot was sub-divided and two new homes were built on the lots to the east. Today, there is just a peekaboo view of the house from Chesterfield but a fuller view from the west.

3371 Chesterfield with two infill homes on either side. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Clay.

Close-up of the Main House of the old Chesterfield School for Boys today. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Clay.

A view of the western and southern facades of 3371 Chesterfield today. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Clay.

Except where indicated, text and images Copyright @ North Shore Heritage and Paul Haston. All rights reserved. Republication in whole or in part is prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder. This includes, particularly, all images reproduced here courtesy of the Hings family.

References:

MONOVA, North Vancouver Museum and Archives. https://monova.ca/archives/

British Columbia City Directories 1860-1955, https://bccd.vpl.ca/

Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Hings

The Canadian Encylopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/donald-lewes-hings

Article on Donald Hings, Guy Cramer, July 2007, https://www.hyperstealth.com/DonHings/Don-Hings-philadelphia-experiment.htm\

Donald Hings webpage, http://www.dlhings.ca/

Anatomy of a Hoax, Jacques Vallee, Journal of Scientific Exploration Vol 8, Number 1, Spring 1994, https://www.scientificexploration.org/docs/8/jse_08_1_vallee.pdf